Today I wanted to talk a little about the idea of “deep POV.” I’ve had a couple authors approach/email me asking questions about the concept. While I was familiar with the idea of point of view (POV) and how to sink deeply into it, I wasn’t uniquely familiar with that terminology. So, I did what I always do when seemingly new knowledge presents itself, I tracked it down.

Typing “Deep POV Books” in Amazon yielded many questionable (in regards to author credibility) self-help type books regarding deep POV. About ten books down on the list, I found some pretty interesting erotica. Scrolling farther down yielded even more eyebrow-raising search results. Anyways, that wasn’t the deep POV I was looking for…

I grabbed the two books (writing books mind you) that had the most reviews regarding the subject. The two books are the following:

- Writing Deep Point of View, by Rayne Hall

- The Writer’s Guide to Realistic Expression, by S.A. Soule (the cover had a blurb about how the book does a whiz-bang job of teaching you about deep POV).

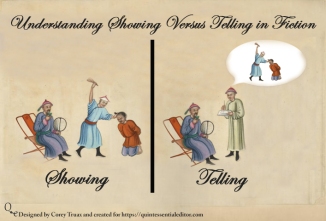

While both books have some decent information, holy macaroni folks, deep POV is just show, don’t tell dressed up in new words. While the showing/telling song and dance is geared toward many facets of writing, this deep POV concept is geared toward characters.

*Sigh*

The marketing folks must by doing a river dance right now. There’s nothing like slapping lipstick on a well-used term and screaming, “I’ve uncovered a new gem! Whadayamean it’s the same as…oh…I see. Okay, one-line show don’t tell and write in deep POV!”

The marketing folks must by doing a river dance right now. There’s nothing like slapping lipstick on a well-used term and screaming, “I’ve uncovered a new gem! Whadayamean it’s the same as…oh…I see. Okay, one-line show don’t tell and write in deep POV!”

Regardless of how used the concept is, if you are unfamiliar with showing versus telling, or deep POV, just know the terms are basically interchangeable in regards to writing characters.

Here are some blog posts I’ve generated regarding showing and telling, if you need a quick fix. The quality of these posts, much like the quality of my brain, is questionable. Though, a few people have found them useful (the posts, not my brain…yet).

Tics and Tells to Show not Tell (talks about using character mannerisms in your writing)

Using Sensory Detail to Enhance Fiction (talks about taking advantage of your senses)

Show vs. Tell & Intensity Scales (talks about the concept and offers a tool to determine when to show or tell)

To be honest, if you are looking for resources on deep POV, you would do well to simply search for solid writing books that have a chapter or so on showing/telling. The two books I listed in the beginning are a great start. S.A. Soule’s book is filled with examples, if that floats your literary boat. If I had to pick a couple of books to recommend on the subject, because you all know I eat my greens, I would point toward:

To be honest, if you are looking for resources on deep POV, you would do well to simply search for solid writing books that have a chapter or so on showing/telling. The two books I listed in the beginning are a great start. S.A. Soule’s book is filled with examples, if that floats your literary boat. If I had to pick a couple of books to recommend on the subject, because you all know I eat my greens, I would point toward:

The Emotion Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Character, by Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi (This book is simply jammed full of tips and examples of how to write believable, visceral character cues. Tackles 70+ different emotions. Great if you can’t deal with emotions…in your writing.)

Mastering Showing and Telling in Your Fiction, by Marcy Kennedy (Confused about the concept? Can’t find a blogger or source of information to solve the problem? Marcy Kennedy does a good job of clearing the fog. Also, this author states that telling isn’t always wrong, or bad, or bad-wrong. Indeed, telling had its place.)

That’s a wrap for today. Sorry to be away for so long; life has been busy (editing, writing, conventions, stay-at-home dadding, military spousing). As time opens up, I’ll spend a little more of it here. Shooting for a post a week here and on the author page, we’ll see if I can pull that off.

Quick question! What books or resources would you all recommend to tackle the idea of deep POV or show don’t tell? I’m always looking for more pieces of information to add to my library. Until we cross quills again, keep reading, keep writing, and as always—stay sharp!

Quick question! What books or resources would you all recommend to tackle the idea of deep POV or show don’t tell? I’m always looking for more pieces of information to add to my library. Until we cross quills again, keep reading, keep writing, and as always—stay sharp!

Tics and tells are a fun way for you to “show” how a character is feeling, or who they are, without having to “tell” the reader. Yes, the quotation marks were purposeful. The concept we’re going to discuss today builds on the foundation of

Tics and tells are a fun way for you to “show” how a character is feeling, or who they are, without having to “tell” the reader. Yes, the quotation marks were purposeful. The concept we’re going to discuss today builds on the foundation of  When it comes to physical traits, I’m thinking beyond just the basic height, hair, skin, gender, and eye color. The basics are a good place to start, but dig deeper. Don’t just think of normal or beautiful traits, find the flaws too.

When it comes to physical traits, I’m thinking beyond just the basic height, hair, skin, gender, and eye color. The basics are a good place to start, but dig deeper. Don’t just think of normal or beautiful traits, find the flaws too. Knowing what your characters are wearing and have on their person is a useful tool. Understanding how they interact with these things is even better. It can also be of use when

Knowing what your characters are wearing and have on their person is a useful tool. Understanding how they interact with these things is even better. It can also be of use when  Here’s an example from my military days. Even from behind in the pitch black with night vision goggles on (which aren’t as whiz-bang as Hollywood would like you to think), I could tell who was with me on a mission by how they were acting. How are they holding their rifle? Are they constantly messing with their helmet straps? Are they constantly moving? Are they constantly leaning on something? These observations allowed me to take green and black humanoid blobs and know who they were.

Here’s an example from my military days. Even from behind in the pitch black with night vision goggles on (which aren’t as whiz-bang as Hollywood would like you to think), I could tell who was with me on a mission by how they were acting. How are they holding their rifle? Are they constantly messing with their helmet straps? Are they constantly moving? Are they constantly leaning on something? These observations allowed me to take green and black humanoid blobs and know who they were. That’s it for today. What suggestions, additions, or ideas would you add to this list? Do you use any of these concepts in your writing? I’d love to talk about it and broaden my depth of knowledge. Until we cross quills again, keep reading, keep writing, and as always—stay sharp!

That’s it for today. What suggestions, additions, or ideas would you add to this list? Do you use any of these concepts in your writing? I’d love to talk about it and broaden my depth of knowledge. Until we cross quills again, keep reading, keep writing, and as always—stay sharp!

When they wrote the scene, the information was clear in their head, it just didn’t make it onto the page. In my own writing, having visual references (like character sheets and templates) reminds me to include those descriptions. I make sure to stick the papers up on the wall in front of me, or somewhere I can see them. This way when the time comes for juicy description, a glance at those papers zeroes me in on important descriptive elements.

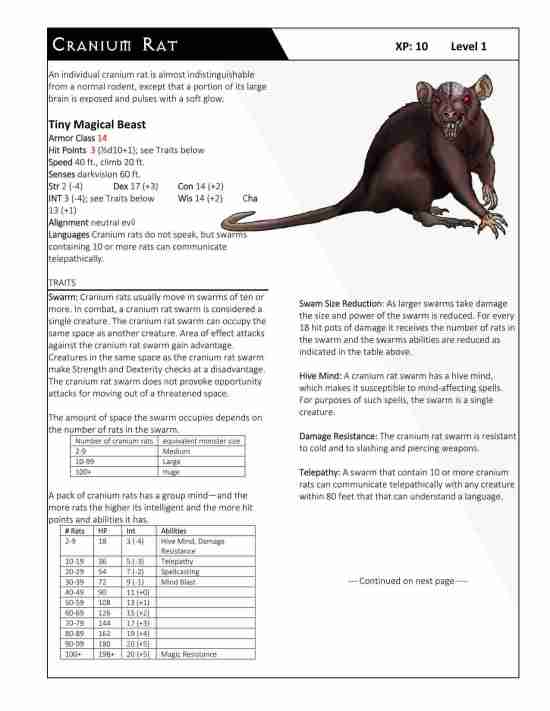

When they wrote the scene, the information was clear in their head, it just didn’t make it onto the page. In my own writing, having visual references (like character sheets and templates) reminds me to include those descriptions. I make sure to stick the papers up on the wall in front of me, or somewhere I can see them. This way when the time comes for juicy description, a glance at those papers zeroes me in on important descriptive elements. That’s it for today. I hope you found some useful tools to create your own monsters here. I’m sure as I continue reading through Writing Monsters some more nuggets of information will accumulate. You can look forward to some posts about flesh chewing chinchillas and what not.

That’s it for today. I hope you found some useful tools to create your own monsters here. I’m sure as I continue reading through Writing Monsters some more nuggets of information will accumulate. You can look forward to some posts about flesh chewing chinchillas and what not.

Well, I’ve scratched the surface with this post about description. It’s a giant beast requiring many knives to bring down. I would love to hear your two cents/insights regarding description and what you feel is vital to the story. Until tomorrow, keep reading, keep writing, and as always – stay sharp!

Well, I’ve scratched the surface with this post about description. It’s a giant beast requiring many knives to bring down. I would love to hear your two cents/insights regarding description and what you feel is vital to the story. Until tomorrow, keep reading, keep writing, and as always – stay sharp!

I‘m not saying my story helped change the world, but these lasers are on ships now…

I‘m not saying my story helped change the world, but these lasers are on ships now…

That’s the breakdown of the concept. I may do one future post on this that discusses some of the misconceptions and beliefs behind the curse. Let me know if this is something any of you are interested in. Have any of you fallen victim to the curse? Have you read the work of someone afflicted with it? I’d love to hear about. I’m also very open to more solutions. Until tomorrow, keep reading, keep writing, and as always – stay sharp!

That’s the breakdown of the concept. I may do one future post on this that discusses some of the misconceptions and beliefs behind the curse. Let me know if this is something any of you are interested in. Have any of you fallen victim to the curse? Have you read the work of someone afflicted with it? I’d love to hear about. I’m also very open to more solutions. Until tomorrow, keep reading, keep writing, and as always – stay sharp!

So if you have sat down and blasted out inches worth of unrelated historical information regarding a world, character, or item — don’t despair. Set it aside and use it as part of your reference material. Try sprinkling in some of it as descriptive beats and reveal the history throughout the course of your book. Maybe you can set up a wiki page for your readers on your blog or website that lists this extra information after the book drops? Or you could use this extra info to market your book before release, like I’ve been doing with my

So if you have sat down and blasted out inches worth of unrelated historical information regarding a world, character, or item — don’t despair. Set it aside and use it as part of your reference material. Try sprinkling in some of it as descriptive beats and reveal the history throughout the course of your book. Maybe you can set up a wiki page for your readers on your blog or website that lists this extra information after the book drops? Or you could use this extra info to market your book before release, like I’ve been doing with my  Are you a sufferer of this affliction? Do you know someone who is? Do you have a cure that works for you? Let me know. While I don’t have a magic elixir, sometimes just addressing it works as a soothing balm. Thanks for reading and be sure to stop by tomorrow. Until then, keep reading, keep writing, and as always – stay sharp!

Are you a sufferer of this affliction? Do you know someone who is? Do you have a cure that works for you? Let me know. While I don’t have a magic elixir, sometimes just addressing it works as a soothing balm. Thanks for reading and be sure to stop by tomorrow. Until then, keep reading, keep writing, and as always – stay sharp!

Change of Location. My office smells a lot differently than the bathroom at a gas station (or so I like to think). When we move our readers from one place to the next, it’s good practice to help them transition by using sensory details. If you find ways to repeat this information throughout the story, sensory cues by themselves can act to quickly prompt the reader to a change in location or character.

Change of Location. My office smells a lot differently than the bathroom at a gas station (or so I like to think). When we move our readers from one place to the next, it’s good practice to help them transition by using sensory details. If you find ways to repeat this information throughout the story, sensory cues by themselves can act to quickly prompt the reader to a change in location or character. Sensory detail to reveal motivation, or as a metaphor. In the movie Gladiator, we see Maximus Decimus Meridius reach down and pick up a handful of sand before he enters the arena. He does this every single time. He grinds the sand into his palms and we can almost feel the grit. He also smells it.

Sensory detail to reveal motivation, or as a metaphor. In the movie Gladiator, we see Maximus Decimus Meridius reach down and pick up a handful of sand before he enters the arena. He does this every single time. He grinds the sand into his palms and we can almost feel the grit. He also smells it. That’s it for today. This was a basic introduction to the concept. In the future, we will break this down and explain some of the components more in-depth. As always, I’m curious about how you all manage to weave sensory information into your projects. Do you actively find yourself smelling and feeling things in an attempt to write about them realistically? Do you just close your eyes and think about them? I’d love to hear about your process. Until tomorrow, keep reading, keep writing, and as always – stay sharp!

That’s it for today. This was a basic introduction to the concept. In the future, we will break this down and explain some of the components more in-depth. As always, I’m curious about how you all manage to weave sensory information into your projects. Do you actively find yourself smelling and feeling things in an attempt to write about them realistically? Do you just close your eyes and think about them? I’d love to hear about your process. Until tomorrow, keep reading, keep writing, and as always – stay sharp!

Hey there you literary lead slingers! I’ve seen more posts on showing versus telling on WordPress than there are tumbleweeds blowing across the dusty plains. That’s a good thing! I was going to list a bunch of references (as usual), but I found an exceptional WordPress heroine who has already done that!

Hey there you literary lead slingers! I’ve seen more posts on showing versus telling on WordPress than there are tumbleweeds blowing across the dusty plains. That’s a good thing! I was going to list a bunch of references (as usual), but I found an exceptional WordPress heroine who has already done that! If I wasn’t so terrified of copyright infringement, I would have placed the fifty-five second clip here. It includes the “bad” guy’s monologue and Tuco’s classic retort…

If I wasn’t so terrified of copyright infringement, I would have placed the fifty-five second clip here. It includes the “bad” guy’s monologue and Tuco’s classic retort…

That’s it for today! I know some of my readers also blog about writing. If you wrote a post on showing versus telling feel free to drop it in the comment box for others to navigate to. I’ll even make a reference section at the end of my article for people to stumble onto your work. Sharing is caring!

That’s it for today! I know some of my readers also blog about writing. If you wrote a post on showing versus telling feel free to drop it in the comment box for others to navigate to. I’ll even make a reference section at the end of my article for people to stumble onto your work. Sharing is caring! As always, I’m curious about your own processes. How do you decide when to show and tell? Is it completely organic (it just kind of happens)? Or do you have a methodology you apply? What do you think of a scaling system like I recreated from Bell’s book? I’d love to hear about it. Until tomorrow, keep reading, keep writing, and as always – stay sharp!

As always, I’m curious about your own processes. How do you decide when to show and tell? Is it completely organic (it just kind of happens)? Or do you have a methodology you apply? What do you think of a scaling system like I recreated from Bell’s book? I’d love to hear about it. Until tomorrow, keep reading, keep writing, and as always – stay sharp! Writers are literary

Writers are literary  Sometimes there is a puff of acrid smoke and we are blinded for days. But every now and then, a miracle happens. The components dissolve and merge together. They glow blue, then purple, then all color fizzles away leaving a glimmering clear liquid. By the gods of dusty vials, you’ve made a potion! Not just any potion. A potion that can change the way a person looks at the world.

Sometimes there is a puff of acrid smoke and we are blinded for days. But every now and then, a miracle happens. The components dissolve and merge together. They glow blue, then purple, then all color fizzles away leaving a glimmering clear liquid. By the gods of dusty vials, you’ve made a potion! Not just any potion. A potion that can change the way a person looks at the world. The apprentice will dutifully follow your instructions in hopes of acquiring the skills you have gathered over the years. Unless we have a dark sense of humor, we must provide detailed description to our apprentice. Lest they themselves be turned into a newt – which may not be entirely a waste. Newts are slimy and hard to find. Perhaps if a steady string of apprentices came through our stock of…er…back to the blog!

The apprentice will dutifully follow your instructions in hopes of acquiring the skills you have gathered over the years. Unless we have a dark sense of humor, we must provide detailed description to our apprentice. Lest they themselves be turned into a newt – which may not be entirely a waste. Newts are slimy and hard to find. Perhaps if a steady string of apprentices came through our stock of…er…back to the blog! You go with number three. Your apprentice nods absently and scurries away leaving the door wide open behind him. With a heavy frown you close the door with your mind, after all, you mixed a telekinetic potion into your chai tea latte earlier – delicious! As the door swings closed, you begin humming the Imperial March (if I want the apothecary to know about Star Wars…he/she knows about Star Wars).

You go with number three. Your apprentice nods absently and scurries away leaving the door wide open behind him. With a heavy frown you close the door with your mind, after all, you mixed a telekinetic potion into your chai tea latte earlier – delicious! As the door swings closed, you begin humming the Imperial March (if I want the apothecary to know about Star Wars…he/she knows about Star Wars). A crows feather? Bloody hell! What went wrong?

A crows feather? Bloody hell! What went wrong?